科技工作者之家

科技工作者之家APP是专注科技人才,知识分享与人才交流的服务平台。

科技工作者之家 2019-03-11

又到了每周一次的 Nature Podcast 时间了!欢迎收听本周由Benjamin Thompson和 Shamini Bundell 带来的一周科学故事,本期播客片段讨论杜鹃的育雏策略。欢迎前往iTunes或你喜欢的其他播客平台下载完整版,随时随地收听一周科研新鲜事。

音频文本:

Host: Shamini Bundell

First up, I’ve been finding out how to raise babies.

Host: Benjamin Thompson

Right, did you get some good child-rearing tips?

Host: Shamini Bundell

Oh yeah, so basically, your main priority as a parent should apparently be to have as many kids as possible and then get them to have as many kids as possible, so you can maximise your evolutionary fitness by multiplying your genetic material.

Host: Benjamin Thompson

Right, I’m sure my significant other will love that approach.

Host: Shamini Bundell

Well, you’ve actually got then a couple of options for different strategies within that. So, you could try the sort of frogs and fish kind of method, which is lay a bunch of eggs, abandon them, and then hope statistically that some of them will make it.

Host: Benjamin Thompson

Well, yes, that’s a strong strategy, sure. But what’s the other option?

Host: Shamini Bundell

Oh, put all your resources into a few offspring and then give them the best chance of flourishing.

Host: Benjamin Thompson

Yeah, I think I’ll probably go with that one.

Host: Shamini Bundell

Typical mammal. Actually, a lot of birds are quite into that strategy too so if you think about a little songbird sitting on her eggs to keep them safe and warm and then feeding the chicks until their nearly full-grown. To me that actually sounds like quite a lot of effort, but I’ve been finding out about a third option, and if you’re lazy like I am, it actually sounds quite good.

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

So, the common cuckoos lay their eggs into the nests of other species of birds, and so the baby cuckoo hatches and is cared for by members of a completely different species.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

So, that’s Christina Riehl from Princeton University. She’s interested in the evolution of this so-called ‘brood parasitism’ – when one individual acts as a parasite on the parental care of another. But the common cuckoo’s method of finding another species and hoodwinking them isn’t the only type of parasitic reproduction. Christina spends a lot of her time in Panama, where she studies another species of cuckoo called the greater ani. This bird has a different reproductive strategy. So, I called her up to find out more.

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

Greater anis are a member of the cuckoo family, but they look a lot like a small crow –they’re black and glossy, they have bright yellow eyes and they have long tails – and most of the time, anis nest communally. They nest in cooperative groups where several pairs build a single nest together and all the females lay their eggs in the same nest and all of the pairs in the group share parental care of the mixed clutch of young.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

Okay, so most of the time, the anis are raising their young cooperatively, and that all sounds very wonderful and harmonious, but your study was actually about the cases where that doesn’t happen.

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

There had been anecdotal reports of brood parasitism, so a female goes to a nest, dumps an egg, leaves and doesn’t provide parental care. So, what we wanted to do in this study was to understand why females act as parasites sometimes, and the benefits of acting as a parasite compared to the benefits of nesting cooperatively and taking care of your young.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

I feel like I would go for the parasitism route – that sounds way easier.

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

Right, it sounds easier, right? So that assumes, of course, that the benefits of parasitising are actually higher than the benefits of cooperating, and so we wanted to test that assumption by tracking the reproduction of females who do each of these strategies and try to understand if parasitism is so beneficial, then why is it that most females nest cooperatively?

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

Right, and so for the study you had things like cameras watching the nests to see who was laying eggs and what happened to them, plus genetic testing of the adults, eggs and chicks, and what did all that reveal?

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

What we found was that most females in the population don’t start off as parasites. In the beginning of the nesting season, almost all of the females in the population join a cooperative group and they try to nest cooperatively and sometimes, in fact quite often, predators find the nests and they eat the eggs or the nestlings. And then that female is faced with a choice – she can either nest again in the same risky place where her eggs were just eaten or she can wait until the next year and just call it awash or she can switch to acting as a parasite. And what we found is actually it’s actually pretty hard to be a parasite. It’s not that easy because it’s true that you don’t have to pay the cost of parental care, but you have to find a host group, you have to put your egg in that nest at exactly the right time, and then you have to hope that that egg actually avoids predation and is raised alongside the host young.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

So, parasitism is not as easy as I might have assumed.

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

That’s right, it seems pretty hard to be a parasite – the timing, the success, and also the number of eggs. If a female nests cooperatively, she’ll lay three or four or five eggs in her own nest. To be a parasite and lay three of four or five eggs, that means you have to either visit the same nest repeatedly and put a bunch of eggs into the same host nest or you have to search and find a bunch of different host nests and lay one egg in each nest, and both of those things are pretty tricky to do. And what we found is it’s usually not a female’s first choice.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

I guess that seems like a relatively simple strategy. They’ve got this cooperative strategy, but if it goes wrong then they sort of resort to parasitism. Is it that simple?

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

Almost, that’s one part of it. The second part though is that some females do this repeatedly. So, we have a long-term dataset from the same population, following the same females over several years, and some females readily act as parasites when their nests are destroyed, and year after year you find their eggs turning up in other nests nearby. And other females never do this even though their nests might be destroyed by predators too. And so, the second part of the story is that when we looked at the overall reproductive success of those two different kinds of females, we found that it was pretty equal. So, females that never parasitise tend to lay slightly more eggs in their own nests than females that do sometimes act as parasites, so it’s essentially a question of where you put your eggs. Do you put them all in your own nest, all in one basket, so to speak, or do you spread them out and spread the risk? And it seems like there are two distinct types of strategies and that the success rates of both of them are about equal.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

And actually, neither strategy seems particularly easy because even with multiple adults around a nest, it’s still tough to protect the chicks and the eggs. There was one video that you got from a camera over a nest that shows a snake sort of sneaking in and swallowing an egg.

Interviewee: Christina Riehl

Yeah, that’s right. I mean I think nest predation really drives a lot of why the anis breed cooperatively as well as why they act as parasites. It’s a tough world out there. It’s hard to raise young. Eggs are very tasty things. Monkeys like to eat eggs, snakes love to eat eggs and so a lot of the different aspects of the anis’ life history from where they nest on the water’s edge to how they nest in groups or when they act as parasites all comes down to how hard it is to avoid predators and to raise young that are not eaten by snakes.

Interviewer: Shamini Bundell

That was Christina Riehl of Princeton University in the US. You can find Christina’s paper at nature.com/nature, along with a News and Views article.ⓝ

Nature Podcast每周为您带来科学世界的全球新闻故事,覆盖众多科研领域,重点讲述Nature期刊上激动人心的研究故事。我们将话筒递给研究背后的科学家,呈现来自Nature记者和编辑的深度分析。在2017年,来自中国的收听和下载超过50万次,居全球第二。

↓↓iPhone用户长按二维码进入iTunes订阅

↓↓安卓用户长按二维码进入推荐平台acast订阅

点击“阅读原文”访问Nature官网收听完整版播客

来源:Nature-Research Nature自然科研

原文链接:https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzAwNTAyMDY0MQ==&mid=2652559057&idx=3&sn=ce14a37d318ebc99d0e12a197306c242&scene=0#wechat_redirect

版权声明:除非特别注明,本站所载内容来源于互联网、微信公众号等公开渠道,不代表本站观点,仅供参考、交流、公益传播之目的。转载的稿件版权归原作者或机构所有,如有侵权,请联系删除。

电话:(010)86409582

邮箱:kejie@scimall.org.cn

光催化,今日《Nature》!

Science/Nature:破局人类生存困境,塑料回收技术登上Nature封面

这篇《Nature》会发光!

新突破! 二维实验系统成功应用于四维材料研究

Nature:凭空(气)发电

Nature-Tsinghua Conference on Inflammation and Cancer 会议通知

重返月球 | Nature Podcast

仿生,登上Nature封面!

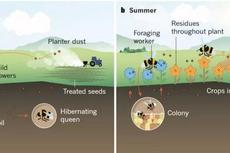

Nature论文称,替代新烟碱的杀虫剂仍会伤害蜂群

Science/Nature,Yaghi/武汉大学邓鹤翔Nature Chem.